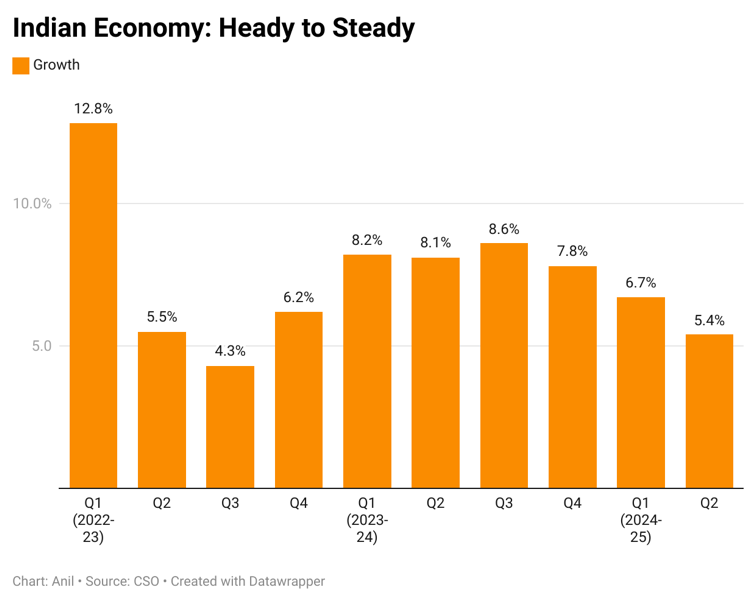

Indian Economy: From Heady to Steady

The latest growth numbers for the Indian economy released by the Central Statistical Office (CSO) have come as a shocker. The economy clocked 5.4% for the second quarter ended September of 2024-25, the lowest rate of growth in seven quarters and way below expectations.

Similarly, India’s retail inflation for October surprised on the upside. It surged to a 14-month high of 6.2%. This is on top of the acceleration in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 3.7% in August to 5.5% in September.

Together, these vital data points suggest that India is facing macroeconomic headwinds. The big question is whether this hiccup is cyclical or structural in nature? In other words, is this setback one-off or is it arising from some chronic challenge encountered by the economy and hence signalling the beginning of a secular slowdown?

Growth Blues

Over the last two years, the Indian economy has been a lighthouse.

Unlike most major economies, India withstood the devastating fallout of the once in a century covid-19 pandemic that hit the world in 2020 and the unprecedented back-to-back economic shocks that followed—breakout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which upended already strained global supply chains and the massive correction initiated by the United States Federal Reserve in interest rates, which ended up exporting inflation to the rest of the world.

The Indian economy rode these setbacks and rebounded to become the fastest growing major economy in the world. In fact, it clocked a very impressive 8.2% growth in 2023-24.

To be sure, after this heady run, the Indian economy has progressively slowed. It clocked 7.8% in the fourth quarter ended March of 2023-24, 6.7% in the quarter ended June of 2024-25 and 5.4% in the latest quarter ended September—the slowest growth in seven quarters.

The country’s chief economic advisor (CEA), Anantha Nageswaran is not fazed. He believes the slowdown in the latest quarter and the first half in general was one-off in nature. According to the CEA, the onset of the general election, which affects spending by both the state and union governments, and an above normal monsoon which dislocated supply networks caused the slowdown.

Addressing a press conference after the release of national income data by CSO, Nageswaran said, “The five-year compounded average growth rate was 4.4% in the second quarter this year, compared to 4.2% in 2023-24 and 3.9% in 2022-23 in the same period. This suggests that the growth in the Indian economy is steady.”

Similarly, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) too has been arguing that the loss of the growth momentum is momentary. Commenting on the variance between the growth projections made by the RBI and the actual estimates by CSO, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said, “The CSO has placed India’s GDP growth at 6.7% in Q1 of 2024-25. Notwithstanding the moderation in growth from the previous quarter and below our projection for Q1, the data shows that the fundamental growth drivers are gaining momentum. This gives us confidence to say that the Indian growth story remains intact.”

Both, Das and Nageswaran, found deteriorating geopolitical risks, and not the domestic economy, as downsides to India’s growth story. In their view, good monsoons, a still robust service sector and emerging green shoots in private sector investment suggest that the Indian economy will recover rapidly in the second half of the year.

Independently, economic analysts argue similarly. According to Pranjul Bhandari, chief economist (India and Indonesia) for HSBC Ltd, India’s growth story is pivoting from a heady to a steady rate of growth.

“We believe the growth exuberance over the past few years was led by the rise of several high-tech sectors (‘New India’). The exuberance in electronics manufacturing, Global Capability Centres, and digital start-ups, led to high growth and incomes at the top of the pyramid. But after a few heady years, the base is rising, and growth in these sectors is normalizing to more sustainable level,” she said in her analyst note, before adding, “Overall GDP growth is gradually converging from 7%+ levels to a more sustainable but still strong ‘potential-growth’ level of around 6.5%. If the improved prospects for agriculture stick, this new growth clip could be more equitably spread.”

The Inflation Shock

In another cause of macroeconomic worry, India’s retail inflation, propelled by high food prices, surged to a 14-month high of 6.2%. Once again, the extent of the upside exceeded official expectations which had argued that retail inflation would rise before beginning a steady decline.

Addressing a recent gathering hosted by the State Bank of India, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, argued that the acceleration in retail inflation was triggered by a surge in prices of select food items that were subject to seasonal variations.

“India periodically and cyclically suffers from adequate supply of perishable commodities. We as a government are making a lot of efforts towards improving supplies by creating storage facilities for perishable commodities. Till we get on the top of that issue you will periodically have this problem of prices of tomatoes, onions and potatoes posing immense stress in a cyclical fashion on inflation,” the FM said.

In October, prices of vegetables, driven by an erratic but abundant monsoon, rose by a staggering 42.7%, oils and fats by 9.5% and fruits by 8.4%.

The FM has a point. India’s core inflation—retail inflation excluding food and energy—was 3.3% in October, compared to the overall retail inflation rate of 6.2%.

Finally it is apparent that the twin macroeconomic shocks are cyclical. In other words, once these one-off shocks wear out, the economy will reclaim its growth momentum.

But it is unlikely to recover to the heady levels of 2023-24. Instead, the growth rate may stabilize to more sustainable yet still very impressive levels.