Make in India is about integrating India into the global value chain: Amitabh Kant

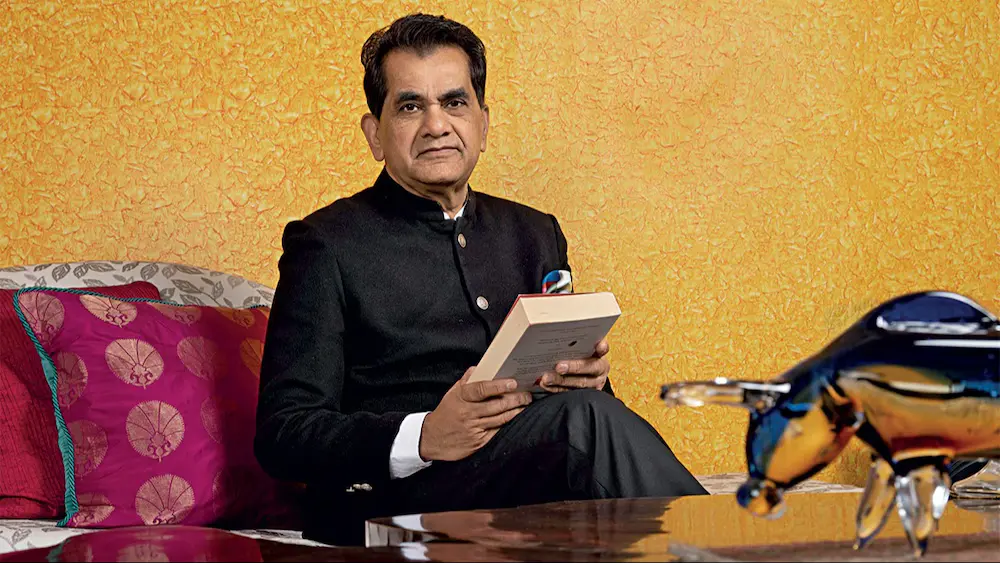

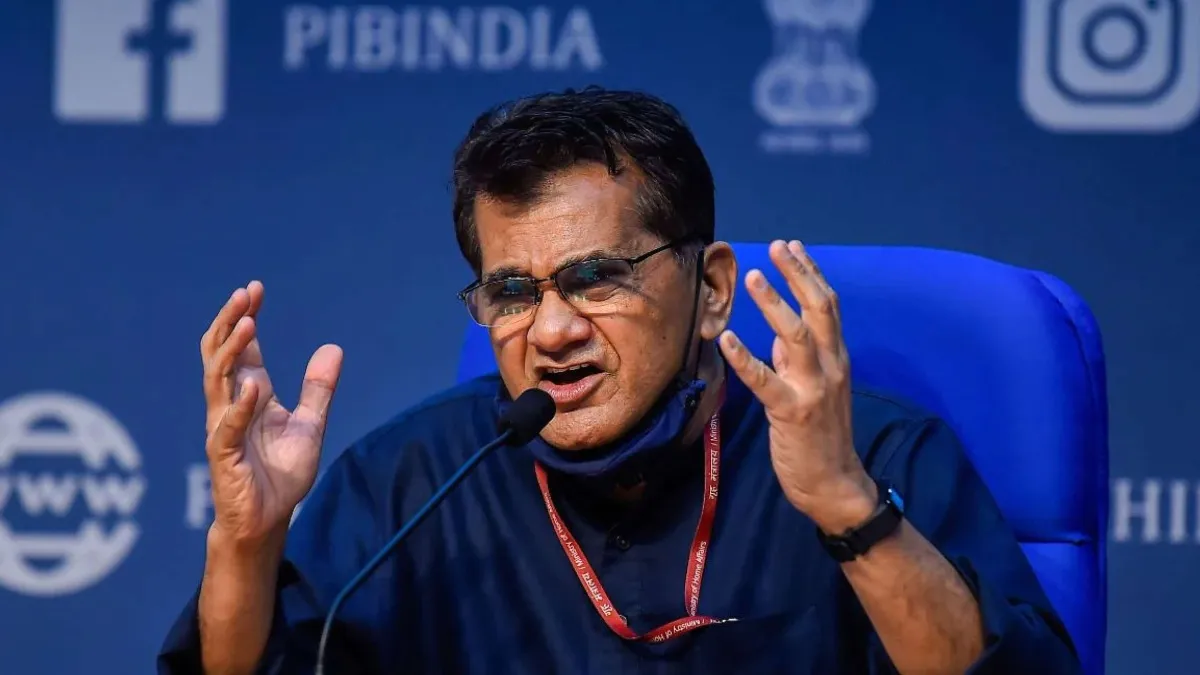

Amitabh Kant, India’s G20 Sherpa, in conversation with Anil Padmanabhan, Editor of India’s Davos Dialogue

India just recorded the 10th anniversary of its flagship “Make in India” programme. To review its progress, we spoke to the programme’s key architect: Amitabh Kant. At present, the veteran bureaucrat is India’s G20 Sherpa. In a freewheeling conversation, Kant dwelled on the successes. But, at the same time he argued that it was imperative for India to press ahead with more policy and process reforms, grow the manufacturing base and create large home-grown champions that are globally competitive. Edited excerpts.

This is the 10th anniversary of the “Make in India” policy. What are your first thoughts, given the fact that you were the architect for this policy move.

We undertook several key initiatives.

First, we launched “Make in India”, with the idea of promoting India as an easy and straightforward place to do business. We focused on streamlining regulatory procedures across the country. Today, many government agencies have gone fully digital, making processes faster and more transparent.

Second, we pushed forward with major reforms like the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), and the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act (RERA). If you look back, these were all significant structural reforms. The lowering of the corporate tax rate was another major change, where the government gave away Rs 1.45 lakh crore in incentives.

The first goal was to improve ease of doing business, and the second was to liberalize the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) regime. Earlier, FDI required multiple levels of approvals with varying limits. We streamlined the process. As a result, FDI inflows into India surged from around $30 billion to nearly $90 billion in 2022-23. We also scrapped the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB), which was a significant move.

A third major development was the reform of our patent and trademark regimes. Previously, it used to take around seven years to get a patent; now, it takes only 14 to 15 months. Our patent regime is now on par with the United States and Japan. On the trademark side, we now issue trademarks within three months. This has been a huge leap forward.

“Make in India” also led to the launch of the Startup India movement. Ten years ago, there were only about 350 startups. Today, there are over 140,000 startups, with more than 40 unicorns. A lot has been achieved in terms of “Make in India,” “Startup India,” and improving ease of doing business.

Additionally, we introduced a state ranking system to encourage competition among states. In the first year, Gujarat was ranked number one. The following year, Andhra Pradesh overtook Gujarat, and in the third year, Telangana surpassed both Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat. The most exciting development, however, was the performance of states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, which moved up from 24th and 25th places to 4th and 5th.

This shows how competition among states is driving improvements, which is crucial for a large country like India.

What about the Production Linked Incentive or PLI scheme? How did this fit in to this policy framework?

It was the next big leap. The aim was to scale manufacturing in India, which is essential for creating large companies that foster backward and forward linkages with MSMEs. The PLI scheme helped increase size and scale in several sectors, particularly electronics and IT manufacturing. Due to the gestation period, the true impact of the scheme will be evident in the next two to three years. Looking ahead, India is well-positioned to create large champions that will drive manufacturing in critical areas. There is a growing realization that we must focus on cutting-edge sectors like artificial intelligence, quantum computing, semiconductors, and green hydrogen. These are areas where the government has launched specific missions, such as the Rs 76,000 crore semiconductor mission and the green hydrogen mission. Never before have we seen such a government so strongly focus on future technologies. If India can become a leader in AI, quantum computing, chip manufacturing, and clean energy through green hydrogen, it will mark a significant step forward in India’s manufacturing journey. A very basic question, what is “Make in India”? There is a body of opinion which argues this is nothing but a strategy of self-reliance. “Make in India” is not about protectionism. Instead, it is about integrating India into the global value chain. Manufacturing thrives when you allow goods to come in from other parts of the world at low tariffs and costs. This enables local manufacturing and, in turn, allows India to re-export to the global market. The idea behind “Make in India” was to position India as a key player in global value chains, making the country a major supplier to the world. To achieve this, it was essential to create a robust manufacturing ecosystem, something that didn’t fully exist before. Issues such as complexity in processes, inadequate infrastructure, delays at ports, and a lack of ease of doing business were significant barriers. Thus, “Make in India” was all about addressing these challenges and positioning India as a crucial part of the global economy.

Why is it that the success of PLI, in say the manufacturing of the iPhone in India, is not replicated in other sectors? Does it have something to do with the fact that Indian business is not competitive as they are still struggling with the legacy of cost of doing business?

This growth will happen in many other sectors over the next two to three years. Apple is the most iconic example, but similar developments will occur in numerous other industries. The beneficiaries of the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, even if they are Indian companies, will see their size and scale expand significantly. They will become major manufacturers and increase their exports. Take, for example, the air conditioning sector, where components were imported. You will soon see India becoming a major manufacturer of these components domestically. In my view, the PLI scheme will yield huge gains in the next two to three years. Our focus should be on thinking big and bold. We need to be clear that It is not about creating 10 companies. Instead, it is about creating 10,000 large companies in India to achieve the necessary size and scale in manufacturing.

This scale of policy change required a fundamental mindset reset in government. What is your insider take on how was this achieved?

At the very first meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, after I presented on the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, the PM emphasized the importance of improving the ease of doing business. He pointed out that there was no political opposition to this, but it would require significant effort, especially in collaboration with various central ministries. The main challenge was not just in changing regulations and procedures, but in shifting the mindset and nudging behavioral change.

For example, when the Employees’ Provident Fund Organization (EPFO) digitized its processes, they continued to require paperwork, effectively duplicating efforts. We had to push hard to ensure that it became fully digital, eliminating the need for physical paperwork.

Similarly, when we introduced real-time digital payments, the Prime Minister instructed me to organize 100 digital melas (fairs) in 100 days, one per day in different cities across India. While we initially objected, the Prime Minister was adamant. In hindsight, that decision provided the momentum we needed to drive digital payments. Today, India accounts for 50% of the world’s digital payments.

Throughout the process, we consistently fostered competition, publicly highlighting the performance of states, and the political will from the top was essential. The Prime Minister was crystal clear that India must become easy and simple to do business, and that the country must evolve into a major manufacturing hub.

India has made significant strides in this direction, although the results, particularly in manufacturing, take time to fully materialize. What we are seeing now is India emerging as a major manufacturer of solar energy products and clean energy technologies. Indian companies are also positioning themselves to become key players in green hydrogen production. Additionally, India is making substantial progress in areas like automobile components, electric vehicle manufacturing, and other related sectors. This is a story that will continue to unfold over the next two to three years.

You mentioned political will. So clearly that was key in the follow through and implementation, right?

Yes, that was very important.

Is this the reason then that we do not see the same enthusiasm at the state level when it comes to process reforms and ease of doing business?

The next phase of reforms needs to focus on the states. It is not just about Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, which have already grown at 10-11%. We need a new set of 10 to 12 champion states to grow at similar rates.

For India to become a $30 trillion economy by 2047, the GDP must increase nine-fold, per capita income needs to grow eight-fold, and manufacturing must grow 16 times. That’s the real challenge—we can’t rely solely on services for growth. Manufacturing must expand, urbanization must accelerate, and we need to build industrial cities and hubs of the future. This will require significant investments in infrastructure, streamlined business processes at the state level, and much faster turnaround times at the ports—many of which are privately operated. Our airports must also evolve into future hubs. To achieve this, India needs to penetrate global markets, with exports playing a crucial role.

For the next three decades, export growth needs to be over 20% annually. If exports are to reach these levels, manufacturing.

So which states, according to you, will be the next champions for India?

I envision states like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka as critical for India’s growth. However, It is important to note that mineral-rich states like Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Bihar hold significant resources. Uttar Pradesh is also a highly populous state and has shown great promise in terms of transformation in recent times. Additionally, Rajasthan, due to its proximity to Delhi, plays a crucial role. If these states can maintain high growth rates of around 10-11% for the next two decades, the country could achieve a growth rate of 10%.

One upside of “Make in India” is the impetus it has given to the creation of defence clusters. Thoughts

India’s defence exports have grown, but they still represent a very small percentage of the global total. For India’s manufacturing sector to be a major success story, defence manufacturing must play a critical role globally. Defence manufacturing drives innovation and product development, so it is essential for India to become a key player in this field. The government has rightly encouraged the Indian Army, Air Force, and Navy to prioritize Indian-made products, which is a welcome shift. Relying on domestic manufacturing rather than imports will have a significant impact, especially if the Indian armed forces begin placing large defence orders with Indian companies. Many of these companies have already contributed substantially to defence manufacturing and have started exporting. However, they haven’t yet received large orders from India’s defence sector due to the lengthy and rigid procedures, which need to be streamlined to allow for faster procurement.

If Indian companies start receiving these orders, they can become global leaders in defence exports. This is how the United States developed its national defence champions, such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing, with government support and cost-plus contracts. India needs to build around 10 national champions in defence manufacturing to follow a similar path. One major obstacle, however, is India’s reliance on the tender process for defence contracts. In the U.S., for example, government auditors are embedded in defence companies, ensuring continuous support rather than going through a new tender process for each contract. This approach encourages innovation and reduces the burden of research and development costs.

India must shift its approach if it wants to drive innovation, research and development, and product development in the defence sector. Additionally, innovation in the defence sector will spill over into other areas, helping India emerge as a more innovative nation overall.

In this context, how do you view the recent deal between the United States and India to design and manufacture compound semiconductors in India?

This is truly groundbreaking, as it will not only lead to supplying the Indian defence sector but also the U.S. government. It is a collaboration between 3rdiTech (an Indian defence startup) and General Atomics, with 3rdiTech comprising a group of young, bright, and dynamic entrepreneurs. This represents a major shift in approach. One of my core beliefs has always been that countries which grew significantly after World War II did so by exporting to the United States—whether it was Japan, Korea, Taiwan, or more recently, China. In fact, China’s rise can be attributed to its relationship with the United States. Therefore, India must work closely with the U.S. in cutting edge areas.

If we collaborate with the United States in areas like AI, semiconductors, and value-added products, and then export these back to the U.S., it would be a significant breakthrough for India. I believe this marks the beginning of that transformative journey.

Geopolitics has turned on its head in the last decade. How has Make in India prepared the country to exploit the opportunity provided by China-plus?

Many companies have begun manufacturing in India, and new investments are flowing into the country. For example, Micron and VinFast in Tamil Nadu, along with companies like First Solar, are all setting up manufacturing operations. However, many of these large corporations are still producing a sizable portion of their goods in China. This is because the U.S. and other countries outsourced much of their manufacturing there. It will take time for this to shift completely.

For India to become a major manufacturing hub on a large scale, beyond just future production, we need to improve in several key areas. India must become highly efficient in terms of production costs, reduce tariff rates, improve logistics to match global standards, and boost productivity levels. These factors are critical for India to become the most cost-effective and productive country in the world.”

How far or how close is India to realizing these objectives that you just listed?

I believe we have made considerable progress. A lot of work has already been done, although the states need a little more encouragement. Over the past decade, we have been driving this growth, and this government has made substantial efforts in infrastructure development. We have been building roads, ports, and airports. In fact, we are the only country in the world constructing about eight airports a year, building approximately 40 kilometers of road, laying about 12 kilometers of railway tracks per day, and developing around three metro systems each year. This is truly remarkable, and it needs to be accelerated and further supported.

Finally, what should be India’s big message at the upcoming World Economic Forum?

Our message should be clear: we are the fastest-growing large economy in the world, and in three years, we will be the third largest. We are driving growth in manufacturing and making significant strides in infrastructure development. While we are a service-sector economy, we are also working to enhance agricultural productivity. As a nation, we are rapidly reforming and improving the quality of life for our citizens: We have lifted 250 million people out of poverty in a decade.